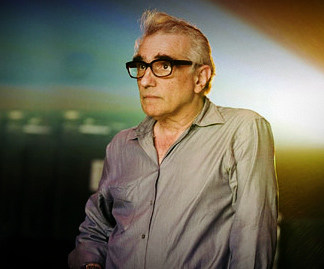

How one of the greatest filmmakers of all time exposes the divine.

There’s been something lurking under the waters of Martin Scorsese’s films since the start of his career. It’s more prominent in some works than in others, but it’s always present. It’s not just his obvious filmmaking prowess. It’s not violence, drugs, sex or profanity. It’s not Italian-American life in New York City. It’s something bigger.

Few people know Scorsese planned to become a priest before pursuing film. Raised in a religious home, he attended Catholic school and spent a year in seminary. His life was once solely dedicated to the gospel.

And though it’s uncertain where his beliefs are today, it is clear he is still working through his faith. Scorsese’s movies have been a lucid autobiography of his convictions and his struggles. He once stated, “My whole life has been movies and religion. That’s it. Nothing else.”

It all started with guilt. Nearly ten years after seminary and attending NYU, Scorsese made Who’s That Knocking at My Door (1968), his first feature film, which explores morality through an Italian-American man’s confusion amid religious convictions and a liberating sexual experience. It may be Scorsese’s most personal movie despite the lack of attention it received.

This would explain why he pursued a similar theme in his 1973 film, Mean Streets. It follows a gangster caught in the middle of two lives: promised prosperity in an obligation to work for his criminal uncle and a commitment to Catholicism, in which he can honestly love his friends and family.

In the opening scene, Charlie’s musings are heard in a voiceover by Scorsese: “You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it on the streets. You do it at home.” Powerful words, as one can only imagine how real and close they were to Scorsese’s heart at the time.

Charlie’s character is different than the stone-faced men of typical crime movies, who care only about riches and power. Like Scorsese, he understands love. He wants to make the right decisions. But with life’s temptations in front of him, the battle is difficult to win.

Three years later, Scorsese continued on his spiritual film journey with Taxi Driver, a glimpse inside the mind of a lonely Vietnam vet. While its religious undertones are slightly ambiguous, this film is a unique character study of a psychopath deeply burdened by the corrupt streets of New York City yet motivated by rejection. The lunatic is very different than previous protagonists, yet there’s still a strong connection between him and Scorsese.

1980‘s Raging Bull is one of Scorsese’s most spiritually riveting movies. He moves away from a theme of guilt and explores the effects of pride. La Motta goes from Middleweight Champion and family man to broken and divorced, losing everything and ending up in prison for involvement with prostitution.

Nevertheless, when hope seems out of reach for the egotistical bombshell, La Motta eventually finds redemption through humility. The movie’s moving finale concludes with an excerpt from John 9: “All I know is that I was blind, and now I can see.” Even though La Motta was a real man, there seems to be no coincidence in Scorsese’s decision to probe his character.

Neither was his decision to make his most spiritual and controversial film, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). The movie, an adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel, is by no means historically or theologically accurate, but it’s not supposed to be. Scorsese warns audiences of this in a disclaimer. The message, however, is overwhelmingly biblical.

Contrasting other movies about the life of Christ, like Mel Gibson’s 2004 interpretation, Jesus is portrayed as the real man he truly was (fully man, fully God). He laughs, dances, shows emotion. And he’s faced with the same temptations all humans are forced to deal with, which makes the film effective. Rather than emphasizing Christ’s physical suffering, it highlights his emotional suffering.

While on the cross, Jesus imagines how satisfying and easy life could’ve been if he had married, raised a family and didn’t have to die. With so many movies centered on characters battling between grace and sin, it’s no surprise Scorsese choose to explore this human side of Christ. Seeing his humility not only expounds upon the necessity and weight of the sacrifice, it makes his final words all the more powerful: “It is accomplished.â€

In 1990, Scorsese returned to his customary genre, while not abandoning spirituality, and made the gangster classic, Goodfellas. This popular film tells the story of real-life mobster Henry Hill. Unlike other Scorsese characters, the intermingling of sacred and sordid is less prominent with Hill. He doesn’t seem to care about anything but money and self. He cheats on his wife, neglects his children, and rats out his best friends.

And there’s no sense of transformation in him. Hill eventually finds safety in a witness protection program, yet he is left empty, not redeemed. Through the life of Hill, Scorsese makes no reservations in revealing the candid consequences of recklessness of power and greed. There’s an inevitable price involved with sin, and he shows that even the most untouchable gangsters in the world can’t escape from it.

Because of violent movies like Goodfellas, Scorsese surprised many people with the 1997 release of Kundun, a story about nonviolence and the life of the 14th Dalai Lama. For others, however, it made sense. Scorsese was dealing with the same spiritual themes prominent in his other films, but in a different way.

Scorsese doesn’t expose the harsh effects of violence through a bloody baptism; he does it through one man’s refusal to take part in it. The Dalai Lama’s life is devoted to love—loving everyone. And even though he is Buddhist, his convictions ring very true to the teachings of Christ. Scorsese’s admiration for the Dalai Lama is surely connected with a yearning for peace and self-control in his personal life.

Despite critical success, Scorsese’s works of the last decade have dealt less with spirituality than predecessors. Gangs of New York has a striking scene in which two enemies simultaneously pray to a god of strength. In The Departed, an undercover cop makes the sign of the cross before risking his life for a fellow officer. But the heavy religious themes of his earlier movies simply aren’t as apparent.

Nevertheless, Shutter Island (out now) is a strong shift back toward tradition. It has all the elements of a twisty psychological thriller with the added bonus of depth. Scorsese doesn’t merely dabble in spirituality, either. The entire movie is allegorical, and there are divine themes under every word, rock and person on the island.

Forgiveness and, inevitably, violence are the clearest, though. Marshall Daniels, the protagonist, is motivated by revenge and sins of the past. Not only that, it all consumes him and his actions to a point of no return. But nothing speaks louder than a question posed at the film’s end …“Which would be worse: to live as a monster, or die as a good man?â€

Shutter Island will, undoubtedly, join the ranks of Scorcese’s most spiritual accomplishments. And his next film—an adaptation of Shusaku Endo’s novel, Silence—is about Jesuit missionaries to Japan; clearly the divine which lurks beneath Scorcese’s films is again making itself known. Despite abandoning his plans to enter the priesthood, Scorsese obviously hasn’t given up on faith or his calling to speak the truth.

http://www.relevantmagazine.com