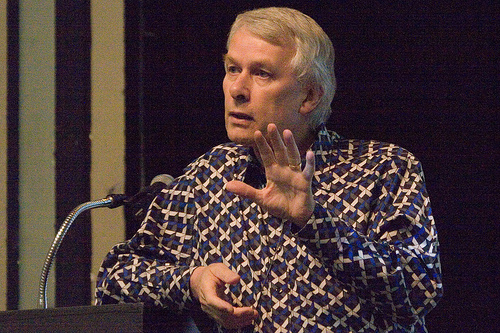

Por reconhecimento geral, o sociólogo Zygmunt Bauman é um dos mais renomados intérpretes da condição humana da época atual. Nascido de pais judeus em 1925 em Poznan, na Polônia (embora resida há muitos anos na Inglaterra), Bauman cunhou a feliz imagem da “modernidade lÃquida” para indicar uma situação de incerteza difusa, em que parece desaparecer qualquer ponto estável de referência.

Por reconhecimento geral, o sociólogo Zygmunt Bauman é um dos mais renomados intérpretes da condição humana da época atual. Nascido de pais judeus em 1925 em Poznan, na Polônia (embora resida há muitos anos na Inglaterra), Bauman cunhou a feliz imagem da “modernidade lÃquida” para indicar uma situação de incerteza difusa, em que parece desaparecer qualquer ponto estável de referência.

[Giulio Brotti, L’Osservatore Romano, 20 out 2013// IHU, 21 out, tradução Moisés Sbardelotto]. Eis a entrevista.

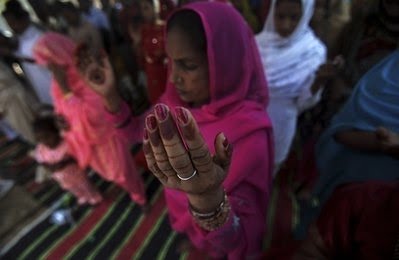

Depois de muitos anos, não parece ter se cumprido a profecia positivista pela qual a dimensão religiosa iria declinar fatalmente, com o progresso da modernidade: na América Latina, por exemplo, o pentecostalismo e o protestantismo evangélico têm um grande sucesso. Mas, quanto ao hemisfério Norte do planeta e à Europa em particular, que traços estão assumindo a fé e a espiritualidade nesta primeira parte do século XXI? A quais mudanças elas poderiam ir ao encontro no futuro próximo?

O meu colega Ulrich Beck, há alguns anos, publicou um livro intitulado Der eigene Gott (em edição italiana, Il Dio personale. La nascita della religiosità secolare [O Deus pessoal. O nascimento da religiosidade secular], Ed. Laterza). O argumento desse livro é o retorno da espiritualidade, ou talvez fosse mais correto dizer: do desejo de espiritualidade na sociedade contemporânea. Falando de um desejo, de um anseio, entende-se que ele se orienta a uma certa representação da espiritualidade, concebida como algo que poderia conferir um sentido pleno às nossas vidas, preenchendo-as.

Evidentemente, constata-se que os prazeres materiais (“da carne”, se diria tempos atrás) não bastam: é preciso um contato com algo que transcenda as nossas ocupações e preocupações cotidianas. No entanto, Beck defende – com razão, acredito eu – que esse retorno à cena da espiritualidade não corresponde necessariamente a uma adesão à s instituições e aos códigos religiosos tradicionais. Ao contrário, a tendência que prevalece hoje não encontra como interlocutores naturais as Igrejas e, talvez, ao contrário do que você sugeria, nem mesmo as inúmeras seitas que confluem no vasto leito do pentecostalismo. Os gostos da nova espiritualidade não propendem pelos dogmas, pelas regras disciplinares compartilhadas: justamente para sublinhar essa novidade, Beck cunhou a fórmula do “Deus pessoal”.

Também poderÃamos falar de uma religião à la carte: sobretudo os jovens operam uma seleção entre diversas fontes, à s vezes decididamente exóticas, em outros casos escavando no interior da tradição católica ou, em menor medida, da anglicana e protestante. Prevalece, contudo, a atitude de hibridizar elementos diferentes, segundo as necessidades particulares e a sensibilidades dos indivÃduos: nessa base, é muito difÃcil que se constituam grupos organizados, comunidades de fé, propriamente ditas.

Trata-se, em essência, de uma religião “psicológica”, destinada a tranquilizar e a consolar o sujeito humano?

É uma reação à instabilidade que caracteriza a vida na modernidade “lÃquida”: em uma época de incessantes e repentinas mudanças, busca-se uma faixa de terra para se poder plantar os pés firmemente. Um dos aspectos mais inquietantes do nosso tempo é que não se conseguem prever as consequências a médio prazo das decisões pessoais: são numerosos demais os fatores que interferem nos nossos projetos. Pensemos no que aconteceu há poucos dias nos Estados Unidos, onde, por causa do déficit do orçamento, centenas de milhares de funcionários públicos foram deixados em casa sem salário. E essa situação também pode ter pesadas recaÃdas na economia mundial inteira, em perspectiva. Busca-se, portanto, um ponto de ancoragem existencial, e essa exigência desemboca, em certos casos, em um neofundamentalismo religioso, mas também pode se expressar de forma diferente: ainda nestes dias, tomamos conhecimento pela imprensa que, na França, o Front National de Marine Le Pen é virtualmente o primeiro partido, segundo as pesquisas que lhe credenciam o favor de 24% dos eleitores, na perspectiva das eleições europeias.

A busca frenética por certezas também pode assumir um aspecto polÃtico?

Certamente, e pode até se traduzir na situação sui generis da polÃtica italiana, em que os partidos estão desesperadamente em busca de alguém para atacar e para desacreditar, não conseguindo se definir de modo positivo, mediante um programa próprio. O problema de uma incerteza difusa, no entanto, certamente não se deixa reduzir a uma questão interna à Itália: a perda de confiança é global, não se refere apenas a determinados partidos ou lÃderes, mas sim ao sistema da democracia representativa. O mundo inteiro entrou em uma fase de interregno, para usar uma expressão de Antonio Gramsci: a humanidade tenciona buscar desesperadamente dentro ou fora de si pontos de apoio para se manter de pé, ou freios para parar o fluxo indistinto que, caso contrário, ameaçaria derrubá-la.

Em nÃvel coletivo, essa necessidade também se encontra no movimento dos Indignados, na Espanha, no Occupy Wall Street, em Nova York, ou nas reuniões na Praça Tahrir, no Cairo. Avança-se à s apalpadelas, no escuro, em busca de modos para poder agir eficazmente: as instituições que tradicionalmente se faziam intérpretes das necessidades e das preocupações dos indivÃduos, traduzindo-os em propostas polÃticas, não parecem mais à altura do desafio. Quanto tempo durará essa passagem e aonde chegaremos? Eu não acredito nos milagres em sentido tradicional, mas acredito nos milagres da realidade, por assim dizer: na abertura de novas estradas onde o percurso parecia bloqueado, na capacidade inventiva dos seres humanos. Nós, porém, por definição, não somos capazes de prever desde agora como essa capacidade poderá se expressar no futuro.

Atualmente, não parece justamente ter se atrofiado a capacidade de pensar sobre o futuro? A expectativa dos tempos messiânicos no judaÃsmo, a das coisas últimas no cristianismo sempre foram um elemento essencial dessas tradições religiosas. Agora, porém, tendemos a avançar à vista, como se o nosso horizonte temporal se reduzisse ao próximo fim de semana. A espiritualidade pode abrir mão da dimensão do futuro? Ela poderá sobreviver em uma condição de presente dilatado?

Não é fácil responder à pergunta que você me faz. Eu me limitaria a salientar que, nos nossos dias, a indústria do consumo propõe substitutos para a espiritualidade tradicional, fruÃveis on the spot, no momento presente. Muitos produtores não se limitam a pôr no mercado bens materiais, mas os cercam com uma aura religiosa. As agências de viagens e as companhias aéreas, por exemplo, publicizam os destinos turÃsticos com a promessa de experiências imortais, de metas paradisÃacas: os seus slogans muitas vezes são variações sobre o tema da imortalidade agora, a ser obtida imediatamente, e não depois que estivermos mortos. Visitando uma certa localidade, hospedando-se em um certo resort, assistindo a um show de rock, pode-se logo experimentar o que você pode imediatamente experimentar o que as pessoas religiosas esperam poder conseguir em outra vida. O modelo é o do café solúvel, que pode ser saboreado em poucos segundos, depois que o pó se dissolveu na água quente. As agências de marketing capitalizam o desejo de uma fuga da incerteza e da desconfiança difusas na modernidade lÃquida: as mercadorias atraem os possÃveis compradores, prometendo-lhes uma redenção da insensatez normal da cotidianidade.

Como o senhor avalia a “novidade” do pontificado do Papa Bergoglio? Há oito meses, os seus gestos e palavras parecem ter induzido uma sensação de feliz desorientação em muitos observadores e comentaristas, crentes e não crentes. Pensemos, por exemplo, na insistência do papa sobre a necessidade de que a Igreja seja pobre, e na responsabilidade do Ocidente para com as populações do Sul do planeta.

Ah, eu estou encantado com o que Francisco [Bauman pronuncia o nome em italiano, sorrindo] está fazendo: acredito que o seu pontificado constitui uma oportunidade, não só para a Igreja Católica, mas para a humanidade inteira. O fato de o lÃder de uma grande confissão religiosa chamar a atenção do Norte do mundo sobre o destino dos mais miseráveis já é de enorme importância. Mas eu também fui ler o que ele afirmava em um texto seu de 1991, Corrupción y pecado (publicado na Itália pela Editrice Missionaria Italiana com o tÃtulo Guarire dalla corruzione, Bolonha, 2013, 64 páginas). Nessas páginas, retornando à parábola evangélica do publicano pecador e do fariseu irrepreensÃvel na implementação das obras da lei, ele sublinha como o relato depõe em favor do primeiro, do coletor de impostos.

Nesse livrinho, há algumas passagens muito bonitas sobre a maior gravidade da corrupção com relação ao pecado: “PoderÃamos dizer – afirma Bergoglio, por exemplo – que o pecado é perdoado; a corrupção não pode ser perdoada. Simplesmente pelo fato de que, na raiz de qualquer atitude corrupta, há um cansaço da transcendência. Diante do Deus que não se cansa de perdoar, o corrupto se ergue como autossuficiente na expressão da sua salvação: cansa-se de pedir perdão”.

A rejeição do legalismo e a capacidade de Jorge Mario Bergoglio de tocar os corações das pessoas lembram a atitude semelhante de João XXIII. O atual papa é intrépido, eu diria, no seu modo de proceder: eu penso nos gestos que ele fez em Lampedusa, nos discursos dedicados aos “fora da casta” do mundo globalizado. Para voltar ao tema do qual havÃamos começado, poderÃamos afirmar que Bergoglio sabe falar à espiritualidade tÃpica do nosso tempo: os seguidores do “Deus pessoal”, com efeito, não estão muito interessados nas prescrições morais emitidas pelos representantes das instituições religiosas, mas desejam reencontrar um sentido na fragmentariedade das suas existências individuais. Ainda estão à espera de um “evangelho”, na acepção original do termo – de uma boa notÃcia.

Os gestos e as palavras do Papa Francisco não poderiam contribuir para “recolocar em ação” justamente a religiosidade individualista do nosso tempo? Não poderiam oferecer-lhe uma perspectiva, impedindo que ela permaneça em uma espécie de limbo, sem relações com a realidade concreta?

É uma hipótese sugestiva a que você prospecta. Pessoalmente, permaneço à espera – com muita esperança e ansiedade, eu diria – dos futuros desenvolvimentos deste pontificado. Também fiquei impressionado com a ênfase que Bergoglio põe na prática do diálogo: um diálogo efetivo, que não deve ser conduzido escolhendo como interlocutores aqueles que, mais ou menos, pensam como você, mas se torna interessante quando você se confronta com pontos de vista realmente diferentes do seu. Nesse caso, realmente pode acontecer que os dialogantes sejam induzidos a modificar as próprias ideias com relação às posições iniciais. Nós temos uma urgente necessidade desse tipo de debate, porque somos chamados a gerir problemas de porte imenso, para os quais não dispomos de soluções já prontas: pensemos nas questões relativas ao fosso entre os ricos e uma considerável parte da população mundial, que ainda vive na miséria; ou na necessidade de frear a exploração indiscriminada dos recursos do planeta, de encontrar uma alternativa para um modelo de desenvolvimento – a expressão já soa irônica – que é claramente insustentável.

Todos esses problemas não param nas fronteiras nacionais: não dizem respeito aos italianos, em vez dos poloneses ou dos chineses, mas a humanidade no seu conjunto. E, de novo, parecem exigir não soluções temporárias, mas sim uma mudança radical do nosso modo de viver. A segunda parte do século passado, no campo econômico, foi dominada por dois pressupostos aparentemente indiscutÃveis, que influenciaram profundamente os comportamentos individuais e coletivos dos seres humanos. O primeira foi que o Produto Interno Bruto de um paÃs era a panaceia para todos os problemas sociais: aumentando o PIB, estes seriam automaticamente resolvidos; se, ao invés, o seu crescimento se bloqueasse ou – Deus me livre! – diminuÃsse, os equilÃbrios sociais entrariam em crise. Em suma, o lema era: para enfrentar um problema coletivo, incrementar o PIB (e, portanto, também o consumo, porque o PIB ainda é medido sobre a quantidade de dinheiro que passa de mão em mão).

Qual era o segundo assunto?

Que a busca da felicidade andava de mãos dadas com o aumento do consumo: os lugares naturais de satisfação pessoal eram as lojas, em vez das relações sociais ou das atividades com as quais cada um podia ser útil aos seus semelhantes, cooperando com eles. Essas duas convicções produziram, de fato, uma grande quantidade de miséria material e espiritual, além de atacar gravemente os recursos naturais do planeta inteiro: de um lado, temos vivido acima dos nossos meios; de outro, descobrimos dolorosamente que a felicidade não pode ser comprada. Portanto, a todos nós hoje se pede que mudemos radicalmente a ordem das nossas vidas. Para expressar essa mesma ideia, o Papa Bergoglio provavelmente usaria um antigo termo da tradição cristã: conversão.